Chapters 11 & 12: Getting Salty

Put simply, Chapter 11 and 12 deal with the topic of salt and how to use it to make your meat better.

Chapter 11: Brining Maximizes Juiciness in Lean Meats

Yet another topic I've heard but not really understood much (this has happened a lot in this book...more than I was expecting..).

A brine is a salt water mixture, but apparently the ratio of salt to water matters. Their ratio is 1 cup salt to 2 gallons of water. ....which seems like a lot so I will do some math... 1 tablespoon of salt to 2 1/4 cups of water.. Ok. I'm tracking. Proceed.

So what is chemically happening with a brine?

It's all about homeostasis. Remember that from 7th grade? Everything wants to be in balance.

Our meat has less salt content than our brining solution. So because of homeostasis, salt from the brine travels into the meat (this is called diffusion). And then when the meat because super salty, it starts to soak up the water to balance (this is called osmosis. --Why are there two terms for the same process? I was clearly not a science major..)

So now we have our meat with added salt and water. There are 3 benefits to this:

- Added water = added juiciness

- Added salt breaks down some cell walls, making meat more tender

- Salt adds seasoning to meat

Chapter 12: Salt Makes Meat Juicy and Skin Crisp

Another chapter about salt, you ask? Yes! But why? Here's what I collected:

Soaking meat in a brine makes meat tender and juicy in 3 ways (see above). But thinking back to Chapter 2 on the Maillard reaction, excess moisture on the skin will prevent the Maillard reaction from happening.

So how do we have our cake steak and eat it too?? Keep the salt. Lose the water.

Now we aren't brining, we are salting. Without water, the first step in this science process is that some water from the meat is actually drawn out of the meat and near the salted skin, created very shallow brine in a sense. Then you know the drill, salt is drawn in, water is drawn back in. And because the mat is not soaking in water, the skin remains dry. Which means, MAILLARD browning.

In the Cook's Illustrated test between brining chicken and salting chicken, both batches received equal praise for juiciness and flavor, but the salted chicken had crispier and more flavorful skin (compared to soggy skin. not good eats).

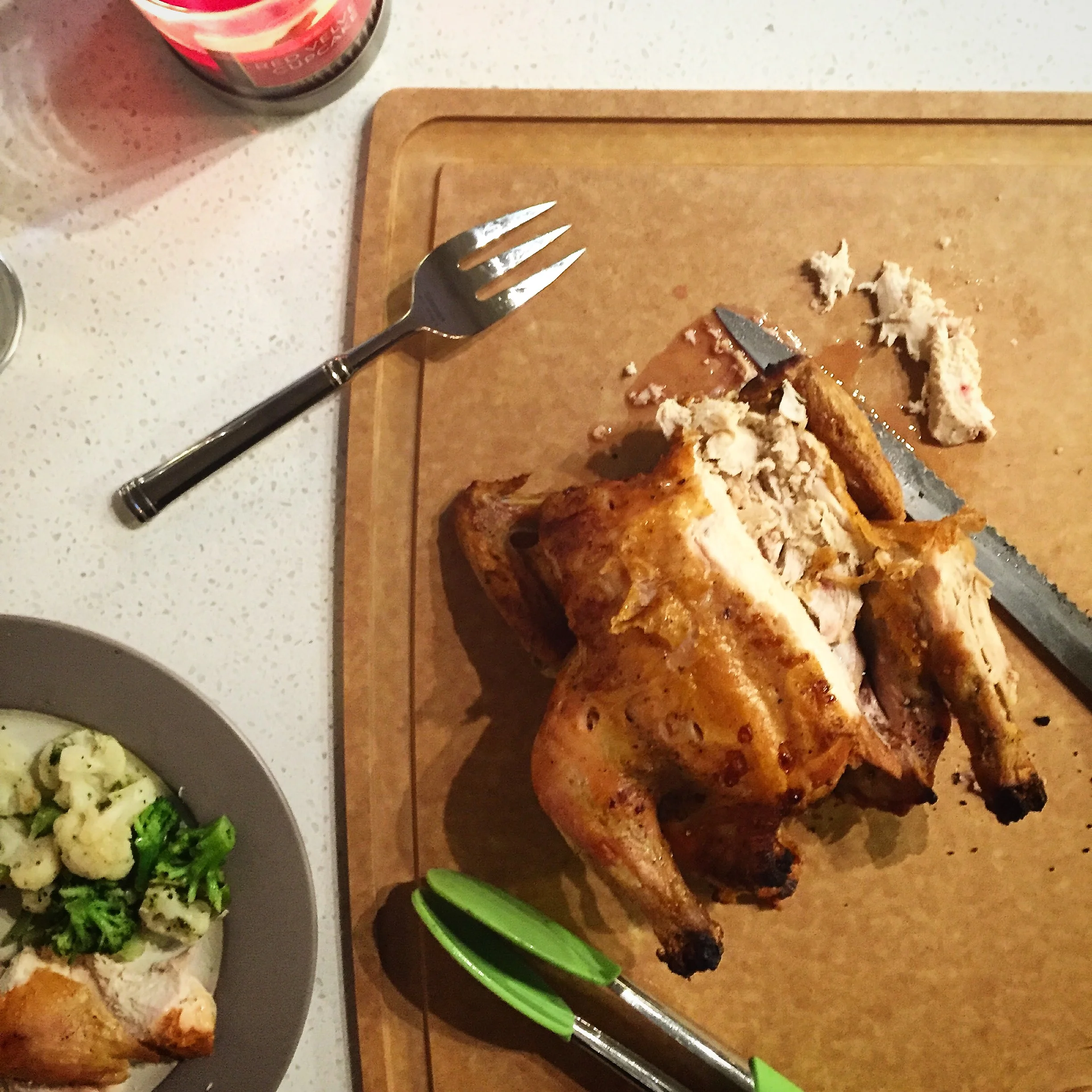

This week's recipe: Crisp Roast Chicken

Salt can bring in a partner in crime to help encourage the Maillard reaction: baking powder. It helps to break down and dehydrate the skin (along with some other sciency things). So I thought I would take a crack at cooking a whole chicken.

A very important detail of brining/salting is that you need to give it time. Too quickly, and the process will not complete. So the night before, I put my rubbed chicken in the fridge:

Have you ever rubbed down a whole chicken? It's an unexpected weird experience. I've handled plenty of chicken, beef, pork, fish, etc., but never whole. I felt the limbs moving, the joints, everything! It truly felt like I was holding an animal. Which was both unsettling and humbling at once. Try it sometime. Gives you an appreciation for what you are eating.

The next night, I baked the chicken. It called for a v-rack. I didn't have one (we literally have no more space for kitchen gadgets right now), so i just put it on a baking sheet.

Turned out crispy juicy and tender!

Ok. Back on the horse. Chapter 13 here I come!